“Most men pursue pleasure with such breathless haste that they hurry past it.” — Soren Kierkegaard (1813-1855)

“Spite and ill-nature are among the most expensive luxuries in life.” — Dr. Samuel Johnson (1709-1784)

The Exercises and Activities

The results you will gain from this program come in many forms and interact synergistically. They don’t merely complement one another in an additive way but in a multiplicative one. For example, the benefits derived from paced breathing, diaphragmatic jogging, passive exhalation, and stretching the diaphragm supplement each other. As you get better at one, you get better at the others. Because these skills are all interrelated, they promote and reinforce each other. This leads to recursive improvement in which the skills form structural platforms, elevating you into an upward spiral.

I hope you now feel that you have a tool kit of actionable exercises and access to deep wells of strength that had previously laid untapped. You may not be sold on all the exercises here. Choose the ones you like the most and practice those for now. As you monitor your progress, you may realize you have largely rehabilitated certain body parts. This may motivate you to go back to other exercises that didn’t seem as appealing at first. In this book, I wrote about what I found helpful to pair with paced breathing. What benefitted me is not necessarily what will best benefit you, so I encourage you to experiment with your own forms of diaphragmatic generalization. If you come up with a new technique, please share it on the web with our online community.

Do keep in mind that a few days of changed perspective might feel like enough to gain the full benefits of Program Peace. However, it may not be sufficient to override your ingrained routines permanently. This system is all about rehearsal. Sustained weekly practice is key. Be persistent, and your efforts will pay off. Some of these activities may feel onerous at first, but they will quickly become comfortable after you have completed them a few times. Most of the exercises in this book are at least partially routinized after the first five sessions. This means they can be done with minimal concentration from that point on (i.e., while on the phone or in front of the TV).

It was incredibly heartening to know that these exercises were slowly making me a stronger, happier person. I knew that I was making daily progress and that something of value was germinating within me. Anticipate positive results with pleasure and excitement. When this happens, the exercises become intrinsically rewarding. As you watch yourself change, you will realize that all these attributes you assumed were genetic and fixed at birth are trainable.

By the end of this book, the first table from Chapter 1 should take on an entirely new meaning. Employ as many of the dominant displays from that table as you can in the exercise below.

Stress and Overexertion

As this book has contended, operating without composure can gravely deplete our health. When we live in distress, we are borrowing health from our future. It is the toll exacted on a methamphetamine addict or a president during an eight-year term. We are talking about a constant state of overexertion in which the body takes a lot of abuse at the expense of your charisma, physique, intelligence, mental health, and spiritual growth.

Distress is an appropriate strategy for an animal with strong evidence that it may die in a few seconds. It is a terrible strategy for you and me. We have discussed how your fight or flight response is seldom directed toward actual fighting or taking flight. Instead, it is directed to bracing, strain, paradoxical breathing, hyperventilation, apneic disturbances, rapid heartbeat, pain, egoism, and submission. To prove to your body that you are not at risk of premature death, you have to divert your focus away from the bad toward gratitude, playfulness, purity, and optimism.

The retraction of the gill by the sea slugs discussed in Chapter 2 shows that they don’t have faith in their world. The slugs exhibiting this defensive reflex in response to being uncontrollably prodded and shocked in the lab are “on high alert.” Their defensive and escape responses are exaggerated, and their responses to positive events are blunted. The slugs that have not been subjected to this don’t show the same defensiveness and are referred to by scientists as “naïve.”

Just because you are not on high alert doesn’t mean you are naïve. Be the sea slug that has seen it all and yet, still knows that the best way to live is never to brace its gills. Don’t treat every threat as novel. Generalize your desensitization to negativity toward every conceivable peril. Do it now. Drop your façade, let your gills hang, keep drawing long, deep inhalations, and learn to expect the best from the world.

Your Transformation

Before Program Peace, I was uncomfortable with my own presence. I exuded tentativeness and a lack of any conviction. I would wring my hands constantly. My dreams were always desperate situations. Once a week, I would wake from sleep yelling in terror. Between the ages of 25 and 30, I would find myself whispering the words “Oh my god” over and over, every day. “That was a nightmare” was my mantra. I had unbearable tension welling up inside of me, gushing out in the form of tortured body language. I hated my home, everything in my room, everything on my desk, all things, and all people because I experienced them through the throes of distressed breathing.

When I turned 20, I discovered that everything hurt a little bit. It hurt to stand up, it hurt to run, it hurt to sit for too long, it hurt to turn my neck, it hurt to use the restroom, it hurt to swallow, and every social interaction hurt. I concluded that this was an irreversible effect of aging. But now I am twice that age, and none of those things hurt. After two years of Program Peace, you should find that you feel much younger than when you started. You will experience a personal metamorphosis internally and externally. You will have acquaintances ask what kind of antianxiety or antidepressant drugs you have been prescribed. Others will ask which cosmetic procedures you have undergone.

Now that I breathe diaphragmatically and send very few subordination displays, the core of my personhood has changed. I used to take dangerous risks that bordered on having a death wish. I never do that today. I am less impulsive, less compulsive, and less codependent. The “imp of the perverse” no longer haunts me, and I no longer play the part of a scapegoat, jester, martyr, or victim. I am no longer consumed with melancholy and self-pity. I am no longer a defeatist or misanthrope. These were recurring themes in my life since childhood. Now, they are distant memories.

All my favorite fictional works involve going on an epic adventure, encountering bad guys, converting them into allies, and then recruiting them to the team. The antagonists in this story are really good guys waiting to be reformed. The thoracic breathing muscles, the sneering muscles, the muscles involved in headaches, and those that make us sick to our stomach are all potential allies. Once converted, your chakra-like modules will become trusted comrades. You will find yourself using them to transform other people into comrades as well.

Breath Mastery

Breathing slowly and deeply with the diaphragm is difficult at first because your respiratory musculature and the nerves that control it have developed their own default pace. You must overcome this default. It is a bit like standing chest-deep in the ocean, trying to keep your balance amid turbulent, unpredictable waves. As you reprogram your breathing, accept the occasional unexpected breaker. Embrace the uneven gushes, the chaotic swells, and the startling surges knowing that, with time, you will control the tides. Permanently.

By way of another analogy, taking a deep diaphragmatic inhalation for more than 10 seconds is a long trek across a barren desert. After the first five seconds, you realize that you’re not going to make it to the other side unless you let go of excess baggage. The baggage consists of those burdensome bracing patterns you are incapable of setting down until you are engrossed in respiration. Try it now. Take a 10-second inhalation. Halfway through, you will feel the strain begin to drop away. When breathing at long intervals, you don’t have the craze and furor to haul this luggage around with you. Every time you cross this desert by taking a prolonged inhalation, you further program your chakra-like modules to let go of their unnecessary burdens.

Illustration 26.1: Concluding analogies.

Allow me a final analogy. You may be familiar with the Greek mythological figure of Sisyphus, a man condemned to rolling a boulder up a hill. As soon as he gets the boulder to the top, it rolls back down, and he must start over—for all eternity. It is a sad story and is considered a tragedy. Now, imagine that Sisyphus didn’t let the boulder roll down the hill. Imagine that he unnecessarily lowered it down using his hands, step by step, at great effort. If this were the case, then the poor guy would never have a chance to rest. Right?

“One must imagine Sisyphus happy.” — Albert Camus (1913-1960)

Relating this back to the body, merely being an animal is hard work. We must labor every day just to provide our bodies with what they require. When stress causes our muscles to remain tense, even when they should be resting, this work becomes Sisyphean. The same goes for breathing. The inhale takes work. Your exhale is your diaphragm’s only chance to relax, so if you keep it braced during those few seconds of outflow, you are completely depriving it of rest. In Exercise 5.1, you practiced allowing your diaphragm to go completely limp during the exhalation, thus giving it the brief respite it needs to stop contracting so that it can regenerate properly. Whenever you notice that your muscles are not passive during rest, imagine letting go of Sisyphus’ boulder and letting it roll down the hill on its own.

This book has laid out eight tenets of peaceful breathing. I think of them as an eightfold path to optimal respiration. Here they are:

The Eight Tenets of Peaceful Breathing:

1) Breathe deeply (high volume): Breathe more fully, breathing all the way in and out.

2) Breathe longer (low frequency): Breathe at longer intervals in which each inhalation and exhalation lasts for more time.

3) Breathe smoothly (continuous flow): Breathe at a steady, slow, constant rate.

5) Exhale passively: Allow your breathing muscles to go limp during each exhalation.

6) Breathe nasally: Breathe through the nose with nostrils flared.

7) Ocean’s Breath: Relax the back of your throat and breathe as if you are fogging up a glass.

8) Breathe with purity of heart: Knowing that you have only the best intentions will put you at peace.

I used to imagine how mind-bogglingly complex it would be to use brain surgery to reduce someone’s propensity for negative thinking. For instance, you cannot just cut out the amygdala because this produces all kinds of unwanted side effects. Instead, it would involve complex submicroscopic manipulations of billions of neurons and trillions of synapses. Where would you start? Diaphragmatic breathing retraining does precisely this but requires no neuroscientific knowledge, no futuristic technology, and no invasive techniques. By placing you in a state of calm from which you can reconceptualize your life, paced breathing will make precise, peace-producing alterations to your cerebral cortex, amygdala, hypothalamus, brainstem, heart, diaphragm, gut, adrenal glands, and other organ systems all over the body. The figure below depicts the curative effects as a virtuous cycle to be contrasted with Figure 5.2.

Figure 26.1: Diaphragmatic breathing creates a virtuous cycle.

A Gene’s Eye View

The scientific evidence suggests that we are here on Earth because a complex molecule got stuck in a rut of self-replication. Our situation as survival machines for DNA can be given a negative or positive valence. Our pain and the pain we inflict on each other make this situation a curse. It is too often a frenzied free-for-all where, as Tennyson said, nature is “red in tooth and claw.” But if we are actively engaged in improving the quality of our life and other sentient beings’ lives, then we transform life from a curse to a blessing. I believe making this transformation gives meaning to life. Your every action, display, and word may have reverberating repercussions on reality that will continue to echo in the physical universe forever. Instead of contributing to trauma through abusive communication, contribute to peace and love.

The nerves that course trauma and pain through our bodies are the reigns by which our selfish genes control us. From our genes’ perspective, happiness and confidence are risky and might get us killed. They are only to be expressed in utopian environments. Our cells operate on the assumption that pain, aggression, and submsssion keep us on the straight and narrow; that living without them is problematic, applicable only when our environment is sending us reliable cues that it is unrealistically hospitable. We must overcome the genetically hardwired negativity bias and fear of relaxation. To do this, we can use diaphragmatic breathing to trick our organs and cells into thinking that our world is an unparalleled paradise. This will give you the elbow room you need to coddle your inner pet, encourage your inner child, and admire your inner caveperson. If we can do this, we all, no matter our age or the extent of our trauma, have the developmental plasticity to become genuinely happy.

Turn Off the Behavioral Inhibition System

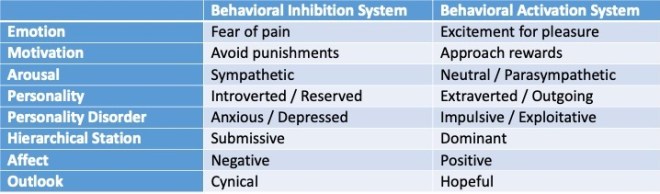

Jeffrey Alan Gray proposed the “biopsychological theory of personality” in 1970, and it remains a widely accepted model. The theory hypothesized two systems: a) the behavioral inhibition system, which stops us from doing things out of fear, and b) the behavioral activation system, which causes us to do things out of positive motivation for reward. He proposed that these two systems are constantly interacting and that people vary in the extent to which these systems influence their behavior.

People who have an overactive behavioral inhibition system spend their life repressing their impulses and restraining their desires. They are sensitive to punishment and perceive it as highly aversive.1 A predisposition toward behavioral inhibition starts in infancy. Toddlers who are behaviorally inhibited have higher heart rates, higher stress hormone levels, tighter vocal cords, and highly reactive amygdalae.2 I would assume that they are also predisposed to distressed breathing.

The behavioral inhibition system has been proposed to be the causal basis of anxiety and depression. It is what keeps us from dancing, laughing, and improvising and pulls us to retreat into our shells.3 The behavioral activation system is the opposite. It promotes approach behavior: cheerfulness, spontaneity, and sociability. As you might have guessed, the exercises in this book aim to activate the behavioral activation system. The following table offers further detail.

Table 26.1: Comparing the Behavioral Inhibition and Activation Systems

You will find that the consequences of these two systems reach into every facet of your life. For instance, as I shot a basketball in my twenties, I would retract from the ball in a cringing motion. This was the behavioral inhibition system in action. Today, my hand follows through and remains briefly in the air at full arm extension. Disinhibiting your follow-through is integral to your ability to score. Be an exhibitionist and treat everything like a game you are playing to win.

We need to be accepting of the fact that we will continue to suffer social failures. We will displease some and not be liked by others. But, if we let our fear of these things lead to inhibition, social defeat will be inevitable. Never choose to withdraw when confronted by a stressor. Always approach. When you find yourself upset, don’t pull away. Push back playfully. You deserve to be loved and respected while being your true, unfiltered self.

See the roadmap for your life as a long series of green lights and ease off the breaks. At every fork in the road, ask yourself: “How would an undamaged, badass version of me deal with this situation?” Start visualizing this person when you think about yourself. When you imagine doing something, picture this person doing it. In time, you will become that person.

Within a pack of mammals, status roles are often initially determined by an animal’s intrinsic energy level. The boisterous youngsters become the pack leaders. These are usually animals that have very low activation of the behavioral inhibition system. The animals that expend more energy in play, foraging, and socializing rise to leadership positions. How can you get your energy levels up? This book has detailed how: how to remove knots, how to reverse frailty, and how not to leak energy.

Dominant people proactively pursue their interests without being hindered by unproductive social fears. They have faith in their ability to succeed and trust that others can’t stop them. They are not embarrassed easily. Neither do they second-guess themselves or worry about what others will think. Don’t stifle the pleasure principle and hide your desires just to get along with others. Like a rambunctious wolf cub, learn to be okay with the social conflict that arises when you try to gratify your wants.

Don’t be a zoo animal released into a wildlife park that still crouches within the invisible confines of its old cage. Having put yourself on a short leash, you are the only one who can take it off. To beat the behavioral inhibition system, you must be spontaneous and do the first thing that comes to mind more often. Don’t be afraid to let your inner animal free. Be resolute in your opinions. Charm people with pizzazz. Make bold and audacious announcements about positive things. Show some backbone, sing with your heart, and live with guts and gusto.

Illustration 26.2: Analogies used in this text.

Being Pure of Heart Will Free You from Retaliation Apprehension

Let me leave you with a description of one final concept from psychology: retaliation apprehension. This is when we feel worried that someone will take what we are saying or doing in the wrong way and get offended. Retaliation apprehension shows in your face, breathing, and body language. It is difficult to describe verbally, but people recognize it immediately when they see it.

My brother has extraordinarily little retaliation apprehension. This is why he can make a personal joke about someone, and they never get mad. Often, it seems that he can say whatever he wants to anyone at any time and get away with it. If I were to say the same thing in the same tone, people would be miffed. My brother can do this because he shows zero concern about the other person retaliating. This allows him to poke fun at people and things in a playful way without offending.

Retaliation apprehension is not just an admission of remorse for known wrongdoing. It is a state of mind we have even when we have done nothing wrong. A tendency toward retaliation apprehension can start very early in life. Many adults have “anxious attachment” issues that stem from their early relationship with their parents. The child with anxious attachment is preoccupied with what pleases and displeases their caretaker. They see their relationship with their mother and father as fragile and they feel at risk for rejection and abandonment. This leads to fear of, and obsession with, the emotions of others.

Refrain from scanning others for a hint of displeasure with you. It is submissive. The best way to do this is to not think about it. Drop any worries about defending yourself. Expecting the other person to like you and not being offended should be presumptive and implicit in your demeanor. Regularly, lowering your defenses in this way should lower your cortisol, blood pressure, and heart rate while raising your feel-good neurotransmitters and HRV. It should also make it easier to breathe with the diaphragm.

Acting with zero retaliation apprehension is one of the most dominant things you can do. Still, it must be authentic. To do it properly, you must have good intentions. This is where being pure of heart (discussed in the last chapter) comes in. When you feel completely secure in the fact that your actions are well intentioned and that you are a force for good, fear of retaliation won’t even cross your mind. It will make social harmony a default that you don’t have to work or strive for. When using the “pure of heart” mindset your retaliation apprehension can be nil even when your behavioral activation system is running at full force.

Conclusion: How to Play the Dominance Game

Humans have a strong instinctual predilection for submissive behavior. When submissive body language goes on for too long, it makes us vulnerable to various forms of muscular tension, which in turn make us vulnerable to disease. This biological propensity should be studied through both basic and applied research and fully addressed by medical science. There should also be implicit and explicit social contracts that limit the extent of submissiveness we “require” from one another in both personal and professional sectors. The more awareness you and I can create, the sooner this will happen.

Hopefully, this book has made it clear that the abysmal repercussions of submission and aggression hamper human potential. If we can minimize our tendencies toward destructive status striving and the social tensions that eat us up inside, we can increase our productiveness. If we can help others do this, we can increase humankind’s productivity and problem-solving potential.

If someone has better posture than we do, we should still stand tall. If someone has a more powerful voice, we should continue to speak powerfully. If someone has a bigger smile, we should keep smiling wholeheartedly. Comparing ourselves to others, like arming ourselves against others, is for animals in “submissive mode.” Put your sword (anger) and shield (rejection sensitivity) down. Let your burdensome armor (retaliation apprehension) drop to the floor. Recognize that the combination of being non-aggressive and non-submissive has made you not only invulnerable but incomparable.

If you are going to play the dominance game, play it with a competitive spirit, play it fairly, play it without malice and without exposing yourself to trauma. Play it breathing diaphragmatically all the while. Don’t flaunt your position or be embarrassed by it. Don’t puff up when things go your way, and don’t shrivel up when they don’t. Think of yourself as dominant without having to dominate. Keep in mind that no one really wins in the end, so there is no reason to keep score. Instead, see competition as “iron sharpening iron.” See it as productive play that makes every participant stronger. Turn contests into friendly cooperative games in which everyone is a teammate whether they know it or not. This will not only earn you friends, but it will also make you indomitable, imperturbable, and self-possessed.

Endnotes

- Braem, S., Duthoo, W., & Notebaert, W. (2013). Punishment sensitivity predicts the impact of punishment on cognitive control. PLoS ONE, 8(9), e74106.

- Moehler, E., Kagan, J., Oelkers-Ax, R., Brunner, R., Poustka, L., Haffner, J., & Resch, F. (2008). Infant predictors of behavioral inhibition. British Journal of Development Psychology, 26(1), 145–150.

- Gray, J. A. (1970). The psychophysiological basis of introversion-extraversion. Behavioral Research and Therapy, 8(3), 249–266.